Art for Art’s Sake

AI art has started to flood the mainstream. But are the results good enough to stand on the stilts of the photography argument?

My wife and I have a ritual of sorts. After a long day spent managing work, chores, and our baby daughter, the little pocket of time we find past ten at night is invested in discussing, bitching, and bickering the happenings of the day over a 90s Bollywood masala film. Either that or it’s a horror film to test how much it can scare us (read: her).

And that’s how, after mundanely scratching our heads on what to watch, we came across a Bollywood entry that seemed to have masala and horror on Netflix: Maa (lit. mother). The banner promoted its lead, Kajol (whom we’ve always adored), and so, no time was wasted in pressing on play.

The premise seemed fine, and the VFX wasn’t impressive in any way, but when the lore bomb in the name of an exposition reel was dropped, I couldn’t help but laugh with disgust.

Why, you ask? The whole bit was AI-generated. The sequence had the unmistakable print of uncanny-valley renders, multiple fingers, and the fractal-like quality that often comes in any intricate pattern AI tools replicate. Hardly adequate to make the hairs on my back stand in fright.

What did scare me, however, was seeing a mainstream entertainer rely on AI rather than actual artists to create computer-generated imagery blended with practical effects. With the prospect of AI-generated short films, film festivals, and India’s first fully AI-generated feature-length films on track to flood the big screens, there is a clear doom awaiting the creative industry.

And that’s just Bollywood. Hollywood, with fresh wounds from the recent SAG-AFTRA strikes against big studios using AI, is seeing a shift, too. On one hand, you have David Fincher using AI as a tool to fix a funky shot for a 4K remaster of Se7en. On the other hand, you have Ridley Scott embracing AI to cut production costs and push creativity in animation.

I belong to Camp Fincher. AI is great as a tool to help the process. It can, for example, prove invaluable for those who lack storyboarding experience, helping them convey their ideas to designers and artists.

But there are many in the AI creativity camp, like Scott. It is these who parade that AI is no different than when photography first came out, challenging then-existing art styles.

So, let’s expose the chink in the armor they think is infallible, shall we?

What is Art?

In the simplest definition, art is expressionism. It’s the way you sketch, paint, brush, carve, chip, or erase—or any other tool verbs you want to use—to give birth to an idea, an imagination, or a scene that sits outside of reality, no matter how photorealistic it is.

Tools on the job here require manual input. You cannot instruct a pencil or charcoal to sketch out a detailed portrait, or ask your collection of paintbrushes to dive into oil and stroke an imagination on canvas as if it were Disney’s Fantasia. Nor can you chisel details of pillows or fabrics rolling on the skin of a bust carved out of marble.

All this takes skill, one honed with patience and practice. You have to hold your tools, feel them as extensions to your hands, and move them on the canvas to achieve a desired result. This applies to all the styles that have ever existed: from cave paintings and rather flat, medieval religious art to realist perspectives of the Renaissance, and even caricatured cartoons, surrealist melts, dadaist chaos, and abstract messes of modern times.

So, when photography first came out, there was a challenge to the hard work of real artists. What was this stupid box of a tool that captured life as it was? There was no room to express the sky as a swirl of stars and midnight velvet, no channel to portray nature in watercolour veils, no motive to express one’s manliness onto their mistress’s face.

As time passed, photography grew into its own medium of expression, a playground to mix light and shadows as they fell on the subjects, and later, a chance to play with colours and tones through digital tools.

It’s this flashpoint of the emergence of photography that many backers of gen AI use as the foundation of their favourite tool.

But is it a tool like the tactile ones we discussed above? Let’s compare the humble pencil to, say, ChatGPT. Both tools can be used to write and to sketch. So, what’s really the difference?

The pencil is more passive. It only leaves a trail of graphite where you crush the tip of its lattice arrangement to break down into a smoky curve. That curve can be a straight line, a circle, a squiggly glyph we call letters, or a complicated combination of pressured strokes and strikes. The end result is dependent on the hand that wields the pencil. All the pencil does is trace the movements of your hands, flex the rotation of your wrists, wiggle at the slightest push of your fingers, and imprint as dark as you press it onto paper.

Compare this to ChatGPT and its sub-models used for image generation, and you see a chasm between the participant and the tool. Your hands do not flex, turn, or do complicated pirouettes on paper. They just type out some words as instructions. The rest is handled by AI. It’s an active yet removed process, no different than I asking an artist to commission a piece for me. Does that make the artist my tool? No. It certainly doesn’t give me any intellectual rights to the finished work. All I get is the title of a patron. I did no work.

Unlike the proud patrons, however, who delight in displaying oil-on-canvas masterpieces they’ve commissioned, the gen AI crowd prefers to label itself artists. They haven’t picked up any pencils, pens, or brushes. No. They’ve only asked their friendly neighbourhood LLM model nicely to draw on their behalf. How they fancily craft their instructions could be . . . erm . . . stretched to call art, but that’s where their interaction ends.

They don’t even own the piece they created, because their AI tool has just replicated something based on millions of illegally breached art styles. Sure, you can bicker about originality in art as an imitation of another; a sincere form of flattery, right? If that vision came from your head and was toiled upon by your hands on paper or canvas, you could go that route.

But with AI, the waters of copyright seem . . . complicated, to say the least.

Prompts vs Photographs

This is where the photography argument gears up into a clash of schools, of sorts. I say “of sorts” because all I see is incompetence leaping on a platform to stand tall with actual talent and hard work.

Not everyone has the skill to create art, but then again, art is not limited to a select few. Yes, there are people who are phenomenal with their brushes, but then there are far more skilled artists who’ve been consistent with their practice to hone their style and skills.

And yet, the AI crowd performs a crude reduction comparing photography with prompting “art,” replete with the pride of an artist.

Here’s how the argument goes: Taking a photo is all about pressing the button. There is no skill involved. It’s the camera’s body that lets the light in and the sensor—or the photographic plate—that captures the image to be processed. There’s no human creativity there.

I appreciate the effort this argument puts in giving artistic weight to AI. But there is a certain skill in handling a camera. It never replaced traditional art forms because it too became a tool to express ideas, albeit with aperture, shutter speed, ISO, and other factors working the same job as a pencil or a brush stroke.

I know the counterargument that bubbles in this wake, that commanding a prompt that tightropes every factor in generating an image is analogous to turning the knobs and dials on a camera body.

Is it, though?

To make art, you need to know the subject and your craft. A still life of a jug and some fruits will be very different when you paint it versus when, say, Monet, Van Gogh, or Dali were to paint it. Even if someone were to photorealistically replicate these objects on canvas, the final rendition would be different from an actual photograph when you go into the minutiae. A photograph from you vs a professional in the field will be vastly dissimilar.

AI, however, just fakes the imagination and creativity by replicating approximations of something based on the style it was asked to copy. It is, however, getting scarily good at it.

But, for the sake of this argument in the guise of an essay, I’ll change my stance and claim that I do know how photography is no different than prompting. Let me prove it to you.

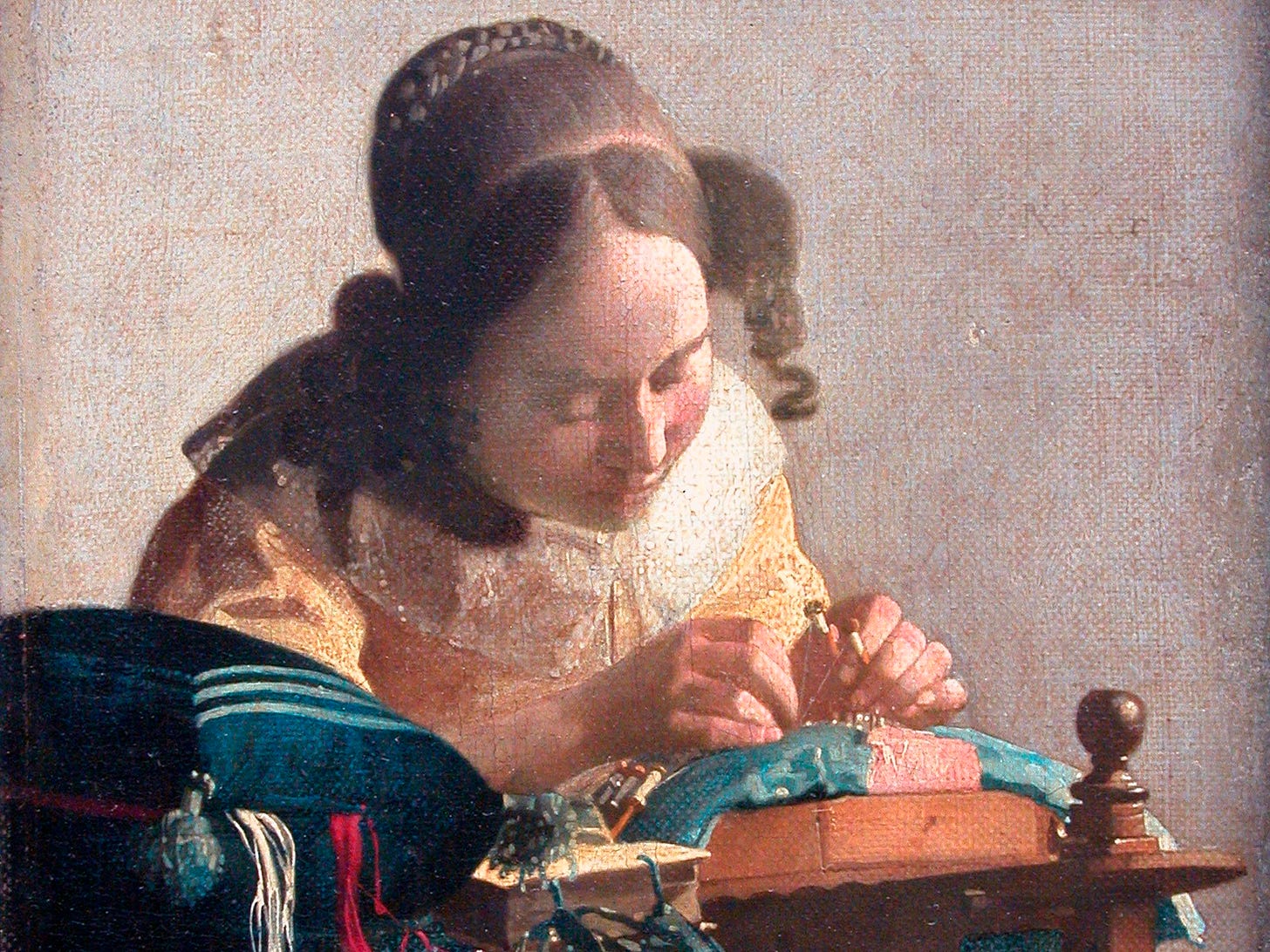

Say I were to go to the Louvre and take a well-lit, highly detailed picture, or stitch multiple photoscans into a greater print, of Vermeer’s Lacemaker. I make sure that the grains and fibers of the canvas, the brushstrokes, the paint colours, and even the exposure are lifelike. Probably chip my nail working the dial to set manual settings. It’s hard work, after all.

The final composition, then, is mine. So what if my photograph is just a copy of Vermeer’s hard work? Doesn’t matter one bit. I lit the scene, I balanced the tone map, I pulled the shutter.

That final result, for art’s sake, and my camera’s, is mine. Vermeer should try to catch up with the times. In his grave, of course.

Now tell me, would you commission me to create a copy of the famous art pieces for you?

Ya a hand drawn Flamingo is better than a headless flamingo assumed to be created by AI https://edition.cnn.com/2024/06/14/style/flamingo-photograph-ai-1839-awards